As large and typically “traditional” organisations start to embark, maintain momentum or pivot on their journey with new ways of working, the buzzwords of “Project to Product” are likely to be in the conversation in your organisation.

One of the primary drivers of this has been the book of the same name from Mik Kersten. Whilst the book is no doubt useful, it does not quite delve into the practical application within your organisation, particularly around various aspects of product management.

In a recent Twitter interaction with Chris Combe, I felt the questions he was asking were very much in-line with questions I had/get asked about in organisations on this journey:

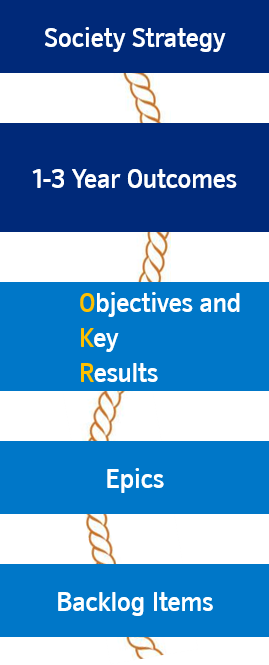

The following is a summary of thinking I’ve been encouraging and questions I’ve been asking in recent weeks (as well as over the past few years in different contexts). These are what I believe to be appropriate nudges in the different conversations that will be happening in the different parts of an organisation on this project to product journey. To be clear, it is not to be confused with a framework, model or method, these are simply prompts (or tricks up your sleeve!) that I believe may help in progressing conversations you may be having.

Defining product

One of the first challenges faced is actually defining what is a product in your context. You don’t need to reinvent the wheel here, with plenty of good collateral out there in the industry already. A starting definition I like to use is:

Product — something that closely meets the demands of a particular market and yields enough value to justify its continued existence. It is characterised by its benefits, features, functions and uses that satisfy the needs of the consumer.

Due to the fact many folks will be used to approaching work from a project perspective, it helps to clearly articulate to people what the differences between the two are. In it’s most simple form, I like to go with:

Project — a temporary endeavour undertaken to create or deliver a solution, service or result. A project is temporary in that it has a defined beginning and end in time, and therefore defined scope and resources.

However, definitions alone are not enough and you will find be left open to interpretation. There is already good information on the key differences out there already, such as this paper from IT Revolution, or this neat graphic from Matt Philip’s blog post:

Further reading -

Be prepared to be able to talk to this at detail with folks, explaining how some of the thinking may work currently in your organisation and what that may look like differently with this lens over the top.

IT Applications (Technology Products)

It’s highly likely given the software lens of the Project to Product book that the immediate focus on product definition will be in Technology/IT. If that’s the case, it might help to elaborate one step further with the following definition I like to use:

Technology Product — commercial and/or internal technology product that adds value to the user. Products may be assembled from other products, using platforms and/or unique components.

I find this definition works quite well in the myriad of application, operations, platform and component teams most large organisations start off with. In particular it allows people to start thinking about what part they may play in the bigger system of work.

SNow way all those are products!

One experience you might have is similar to what I’ve observed (in two large organisations now) which is where folks tend to fall into the trap of thinking that just because you can raise a ticket against something in ServiceNow (SNow), then that’s a product. In my role prior to Nationwide, some IT Service Management folks (who actually were one of the strongest advocates in moving to this way of working) were trying to get ahead of the curve and unfortunately made this same mistake. They extracted the configuration item records from ServiceNow, finding there were over 800 applications in our IT estate. Which prompted a flabbergasted view of, “we’ve got 800+ products, so we’re going to have 800+ teams?!?!”

First of all, chances are pretty high that a number of these are not actually products! As part of this move to new ways of working, use it as an opportunity to consolidate your estate (or what will hopefully become known as your product portfolio). For one, you’re likely to find items in the list that are already decommissioned yet the records have not been updated.

Another question is around usage — this is where you refer back to your definition of product. How do you know it’s used? Do you have any telemetry that points to that? In the example I mentioned there was practically no analytics on usage for nearly all 800+ applications. As a proxy, we took the decision to start with incident data, making the assumption that those applications with higher call volumes were likely to have high usage. Those without an incident raised for 2 years are candidates to investigate further, becoming retired and not a part of our product world.

You can also use this as a learning point when incrementally moving to product teams. For those initial pilots, a key data point should be embedding that product telemetry to validate those assumptions made on those “products”. Depending on your technology, some of this can be more sophisticated (more modern applications will tell you pretty much everything that happens on the user journey), whereas for older, legacy technology you may have to rely on proxy measures (e.g. number of logins).

Grouping products

Even with a consolidated list, this still doesn’t mean a 1:1 ratio for every product and product team. It’s likely a number of these products will be releasing less frequently (maybe monthly or quarterly). This does not mean you are in “BAU” or “maintenance mode” (for more on this — please read Steve Smith’s latest post), which is another unlearning needed. What you can do is take these smaller, less frequently releasing products and group them into a product family. A definition I like to use for this is:

Product Family — a logical grouping of smaller products that address a similar business need in different but related ways. They may or may not align to a specific business unit or department.

What you may then choose to do is logically group these products / product families further. This however is highly context dependent, so be prepared to get this wrong! In Nationwide we use Member Needs Streams, within three long-lived Missions. This absolutely works for those in the Missions working to delight Members needs, however becomes more troublesome if you’re in an area working to the needs of colleagues rather than members (for example, we have a shared technology platform area with multiple teams). You may choose to go with Value Streams, however this can often be misinterpreted. I’ve had this experience in two organisations, prior to Nationwide the organisation simply couldn’t get their head around what a value stream truly was. More recently, within Nationwide, some folks have baulked at a value stream as it is wrongly misinterpreted as extracting value from members, aka treating them the same as shareholders, which is not what we want and is a distinguishing factor for us being a mutual.

In making this decision, definitely explore different approaches. For example, your organisation may even have a business capability or value chain defined already. Whatever you chose, be mindful that it will likely be wrongly misinterpreted. Be armed with real examples of what it is and is not, specific to your context.

Products for other departments (i.e. not just IT!)

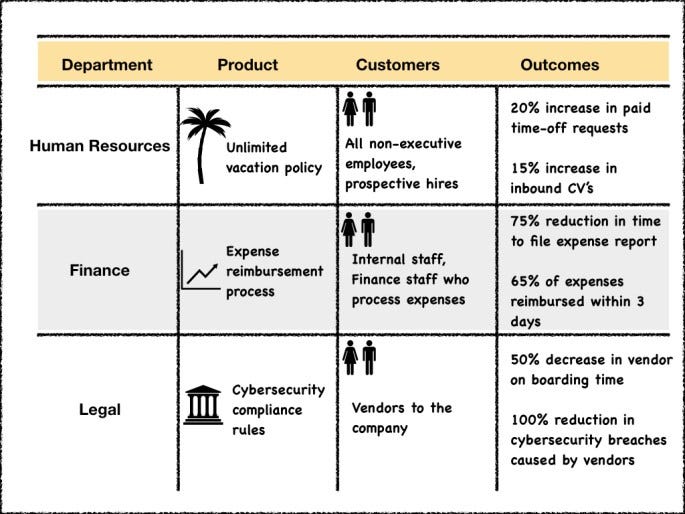

Once you’re aligned on product definition, questions will arise from those teams who do not ‘build’ technology (IT) products. What products do they have? Thankfully there is again thinking already in this space, with this great blog from Jeff Gothelf that articulates how other departments in the organisation can think about what they offer to the rest of the organisation as “products”.

Source:

Do HR, Finance and Legal make products?

When we consider our context, within Nationwide we recently announced changes to our approach with remote working, going with the slogan of Locate for our day. This is essentially the formal recognition that we’re now increasingly seeing hybrid events with our way of working, remote and flexible working is here to stay, however there will be instances where in person collaboration may be more effective, therefore it’s a collective (our) decision on work location. You could articulate this with a product lens, like so:

Defining non-technology products may be something that comes later on the journey (which is fine!) but experience tells me it helps to have applied this thinking to your organisation so that when the conversation inevitably happens, you have some ready made examples.

Not everything is a product/not everyone will be a Product Manager

Another trap to avoid is going too far with your ‘product’ definition. Consider your typical enterprise applications used by pretty much everyone, taking Microsoft Teams as an example. It would be unfair (and not true) to put someone in a Product Manager role and say they are the Product Manager for MS Teams. Imagine introducing yourself at a conference to peers as the Product Manager for MS Teams (when working at say, Nationwide) — I’m sure that would confuse a lot of people! If you can’t make priority decisions around what to build then don’t kid yourself (or let others fool you!) into thinking you’re a Product Manager. This will only damage your experience and credibility when you do move into a product role. Similarly, don’t move people into a Product Manager role and not be clear on what the products are. This is again unfair and setting people up to fail, feeling lost in their new role.

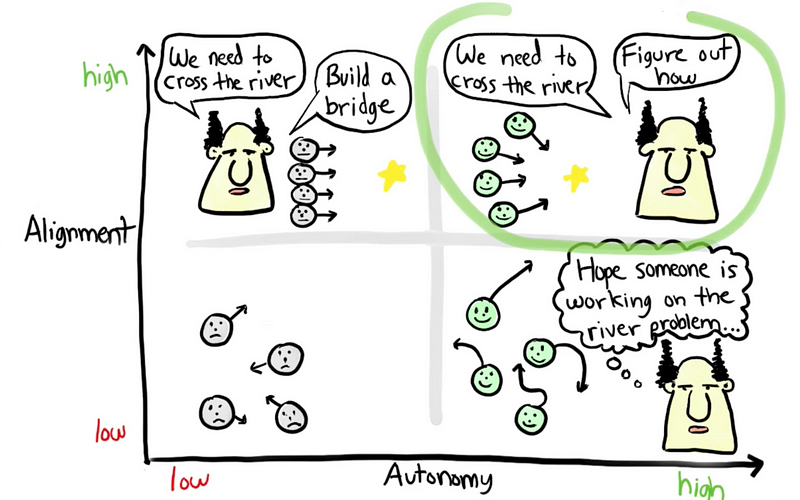

Product Teams

With clarity on what a product is and the types of products you have in your organisation, it’s also important to consider what your organisation means by product teams. In my view, the best description of a product team (or what you should be aspiring to get to) is from Marty Cagan, in both the book Inspired and the Silicon Valley Product Group (SVPG) blog (here and here).

Unfortunately, most people don’t have time (or at times, a desire!) to do further reading, therefore something quick and visual for people to grasp is likely to aid your efforts. John Cutler has a handy infographic and supporting blog around the journey to product teams:

Source:

In my experience, use this to sense check where you are currently, as well as inform your future experiments in ‘types’ of product team. It also isn’t a model, so don’t think you need to just go to the next row down, you can skip ahead a few rows if you want to!

Tailoring language to your context is important too, for example ‘Run’ may be ‘Ops’ in your world — help it make sense to people who have never done this before, avoid new jargon unless you need to do that in order to make a clear distinction between x and y. The second from last row (Product Team w/ “mini CEO”) may be the end state for a lot of teams in your organisation, but it doesn’t mean you can’t experiment with having some ‘truly’ Product Teams (the last row).

Product Management Capability

A final nudge for me would be focusing on capability uplift within your people. This way of working will excite people, in particular those who like the idea of/have read about Product Management as a career. Whilst you should definitely capitalise on this momentum and positivity, it’s important to ensure you have people experienced in your organisation flying the flag / defining what “good” looks like from a product management perspective.

If your people are learning from YouTube videos (rather than peers) or taking on a role not knowing what Products they’ll be Product Managers for, or your most senior people in the “Product” part of the organisation (Community of Practice or Centre of Excellence) have never been in a product role, chances are your efforts will fall flat. And no, before you think about it, this ‘expertise’ will not come from the big 4! Be prepared to have to recruit externally to supplement that in-house enthusiasm with a group of people who can steer the ship in the right direction.

Summary

Hopefully this helps you and your context with nudging some of your thoughts in the right direction. Like I said it is by no means a model or “copy and paste” job, simply learnings from a practitioner.

What about your own experiences? Does any of the above align with what you have experienced? Have I missed things you feel are important nudges too? Let me know in the comments :)